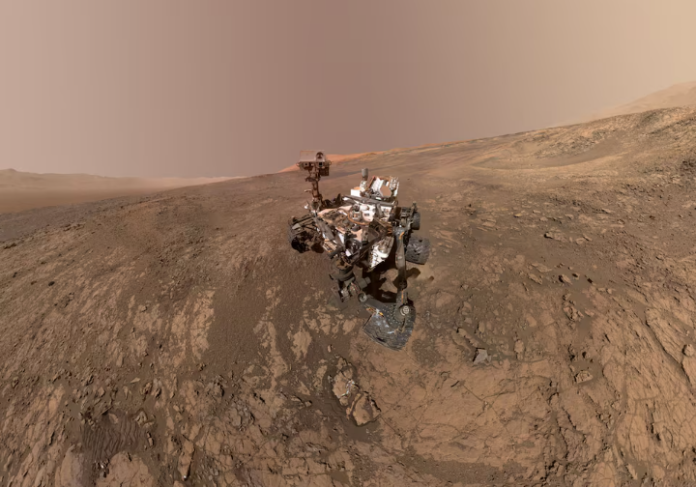

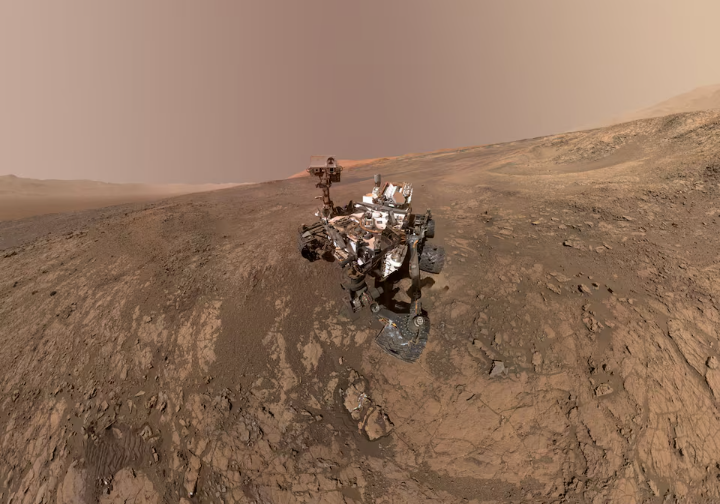

In a stunning scientific breakthrough, NASA’s Curiosity rover has uncovered strong evidence suggesting that Mars—now a dry, barren world—was once a warm, wet planet with large bodies of water and possibly life.

This discovery centers around a mineral called siderite, an iron carbonate compound found in rock samples from Gale Crater, a massive impact basin with a central mountain. These findings, published in Science, deepen our understanding of the Red Planet’s ancient climate and the mysterious disappearance of its dense, carbon-rich atmosphere.

A New Window into Mars’ Watery Past

The Curiosity rover, which landed on Mars in 2012, drilled into Martian rocks at three different sites between 2022 and 2023. In each location, it detected siderite—an indicator that Mars once had a greenhouse effect strong enough to support liquid water on its surface. The rocks showed up to 10.5% siderite by weight, confirming the presence of a long-lost carbon cycle that once made Mars more Earth-like.

Siderite forms when iron interacts with carbon dioxide and water. Its presence in ancient Martian sediments points to a time when Mars had a thick atmosphere filled with carbon dioxide, which would have trapped heat and allowed water to remain in liquid form. This is a crucial clue to understanding how Mars transitioned from a potentially habitable planet to the cold desert it is today.

Why It Matters

While satellite surveys and rover missions had previously found little evidence of carbonate minerals on Mars, this new discovery changes the game. According to Dr. Benjamin Tutolo, a University of Calgary geochemist and lead author of the study, the Martian carbon cycle appears to have been severely imbalanced. That means more carbon dioxide was locked into rocks than was released back into the atmosphere—a process that could explain Mars’ drastic climate change.

“This is one of the most important clues we’ve ever found about where Mars’ ancient atmosphere went,” said Tutolo.

Global Implications

Since similar rocks have been identified across Mars, scientists believe these carbon-rich materials could exist planet-wide. That would mean a vast amount of Mars’ ancient carbon is hidden underground, entombed in rock, instead of floating in its now-thin atmosphere.

Researchers also think these findings could help refine models of Martian climate evolution. While Earth has plate tectonics to help recycle carbon, Mars does not. That could explain why its climate shifted so dramatically—carbon was buried in rock and never released again.

The Bigger Picture

Co-author Dr. Edwin Kite of the University of Chicago calls Mars’ transformation “the largest-known environmental catastrophe.” Understanding where its atmosphere went is not just an academic question—it could tell us whether Mars ever hosted life and how long it may have lasted.

The Curiosity rover’s discovery brings us one step closer to answering one of science’s biggest mysteries: was Mars once alive?